Industry Trends

Largest Transactions Closed

- Target

- Buyer

- Value($mm)

Last updated:

If you are a business owner contemplating the sale of your company, one of the most important terms to negotiate is net working capital, because it affects the value of the acquisition. The target net working capital your business must have at the close of the sale should be outlined in the letter of intent (LOI). The purpose of this approach is to ensure that owners operate the business as they would normally rather than dramatically decrease working capital and increase the cash they get to keep.

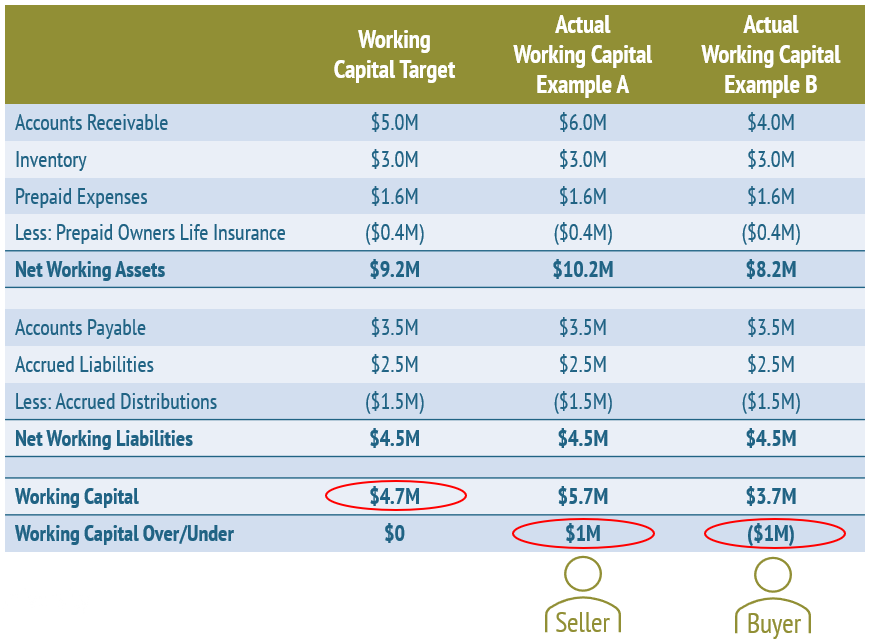

Working capital typically comprises the total of receivables, inventory, and prepaid expenses, less accounts payable and accrued liabilities. At the close, if the owner delivers an amount higher than the agreed-upon target, the owner will receive the difference — but if the owner delivers less than the target, then either the purchase price is reduced or cash is left in the business. In other words, the working capital gets trued up or down after the close, per the agreed-upon terms of the purchase agreement.

Buyers tend to examine the components of a working capital calculation closely and will seek to exclude from the transaction certain elements, such as:

Therefore, as a business owner, you want to analyze the breakdown of your working capital accounts to determine what a seller would view as essential to business growth. Which of the components listed above are needed to generate revenues for the business? What is the status of various metrics (averages and medians) over varying lengths of time? Examining these aspects of your business will tell you if escalating working capital needs are driving your continuous growth — or if you have managed to grow your business with relatively level working capital needs.

This analysis will then inform the line-item breakdowns exhibited in your LOI, so there is no confusion at the close regarding which items are transferred to the buyer and which remain in your control.

Now that you know how to calculate your working capital, you must determine the target. Your historical working capital levels are reviewed over the last several years monthly. The result should indicate whether your working capital level is trending up or down, consistent, or cyclical. These numbers are then analyzed using averages and median values over several time frames, usually 3, 6, or 12-month averages or medians. Recent movements in working capital will normally dictate the length of time. The target working capital needed and established in the LOI is the amount needed to support the projected growth of your company.

Consider the following example of the sale of an operating business. When reviewing current assets on the balance sheet, the buyer discovers that one portion of the prepaid expenses is for the seller’s life insurance policy, which will not transfer as part of the sale. This balance sheet item is then removed from the list of working capital assets.

The buyer also discovers, in the business’s current liabilities, an accrued distribution. Because this distribution will still be paid out to the seller of the company and is not part of the normal expenses incurred to generate revenues, it is removed from the list of working capital liabilities.

The result is a net working capital target of $4.7 million.

In Actual Working Capital Example A (see table), the actual working capital delivered at the close is $5.7 million due to a $1 million increase in accounts receivable due to increased sales. This means the seller receives an additional $1 million at closing.

In Actual Working Capital Example B, accounts receivable have decreased to $4 million as the seller has been able to collect these faster than normal, which results in a decrease to $3.7 million for the net working capital delivered at closing. As a result, the buyer will pay $1 million less for the business.

When closing the sale of your business, you will provide an estimated balance sheet that lists all the line-item accounts for your working capital. Your purchase agreement should provide for a true-up period, when you must finalize your financial statements to determine the true level of working capital at closing and whether the seller or the buyer should receive any additional funds.

One Final Point

As you review your working capital needs while considering a sale, remember to keep running your business as usual. Both the rapid collection of accounts receivable and the delayed payment of accounts payable will artificially inflate your cash balance and force you to leave cash in the company — which certainly is not a desirable outcome.

Accounting for working capital according to the terms outlined in the LOI will result in easier negotiations over the working capital target and create fewer post-closing adjustments. Sellers should have a skilled investment banker to correctly calculate and define net working capital and evaluate and negotiate the target working capital.